BOOK

REVIEW: ‘Super-Forecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction’, by Philip

Tetlock & Dan Gardner

As a

Market Analyst – having worked in a variety of environments from global

businesses to academia, consultancy to the military – forecasting is a crucial

skill; and, according to this book, "forecasting

is a skill that can be cultivated."

In one of those aforementioned, cliché-ridden, environments I have oft heard

such statements as: “We’re here to

forecast the weather, not read the news”; or, even more self-aggrandisingly

amusing: “We are prophets, not historians.”

Whatever; it remains the case that a central tenet of the role of an

Intelligence Analyst is to make assessments about the future.

But,

fascinatingly, the central premise of this superb book, ‘Super-Forecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction’, is that,

actually, those who are often trumpeted as ‘experts’ at such things – from

economists, to political journalists, to the CIA – are actually no better at it

than laymen or, even, “a dart-throwing

chimp.” OK, it’s a lot more nuanced than that, as the author Philip Tetlock

– whose research coined the infamous anecdote about that talented chimp – would

point out, but the point stands.

Super-Forecasting presents the lessons of Tetlock’s

research, particularly since he established the Good Judgement Project (GJP), and invited volunteers to sign up to

forecast the future – around twenty thousand did so and some, the super-forecasters (top 2%), stood out

from the pack: from bird-watchers to engineers, from film-makers to retirees,

from housewives to factory workers. He entered the ‘team’ into a forecasting

tournament run by the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA),

reporting to the Director of National Intelligence in the US, which was

intended to improve the forecasting of the intelligence community.

And his

eclectic team did extremely well: “In

year 1, GJP beat the official control group by 60%. In year 2, we beat the

control group by 78%. GJP also beat its university-affiliated competitors…by

hefty margins, from 30% to 70%, and even outperformed professional intelligence

analysts with access to classified data.”[1]

In

Britain this is timely, as I’m not sure if ‘experts’ have ever had it tougher

than they have of late, particularly in the political sphere. At the time of

writing (August 2016), we have recently seen: pollsters call the 2015 General

Election wrong, then call the EU Referendum wrong, alongside politicians and economists

making all sorts of scatter-gun forecasts about the implications of the EU

Referendum – from plunging consumer-confidence, to an immediate recession, to

collapsing stock markets – that have thus far been wrong.[2] “People in this country have had enough of

experts”, said Michael Gove; or, as Allister Heath put it in The Telegraph, “The ‘experts’ were not just a little bit wrong, but horrendously,

hopelessly so…The forecasters are on another planet.” Tetlock had ‘lunch

with the FT’[3]

soon after, and Brexit was one of the subjects: interestingly, super-forecasters called this one wrong.

I, on the other hand, nailed it at 52% Leave, with my own forecasts switching

from Remain to Leave about three weeks out! (Continuous revision of forecasts

is an important factor, according to the book: “When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do?”)

|

| Evidence of my forecast, from WhatsApp! |

So it’s

in this context that the key lesson from Super-Forecasting

is so powerful: those who are more intelligent than average (but not “geniuses”), more numerate than average,

well- and widely-read, and who deploy a logical methodology, can be super-forecasters and superior to the

‘experts’ and the talking heads on TV. They are “foxes”, with wide and shallow perspectives; rather than “hedgehogs”, with depth and expertise in

a narrow field[4].

In the words of the author:

“What makes them so good is less

what they are than what they do – the hard work of research, the careful

thought and self-criticism, the gathering and synthesizing of other

perspectives, the granular judgements and relentless updating.”[5]

And this

is where we find the chink of inspirational light for industry Challengers and

SMEs too: there is no reason why these businesses cannot be better at this than

their larger competitors, as a source of competitive advantage. Indeed, for a

couple of reasons, it is imperative that they are! Ultimately, the purpose of

forecasting is to identify opportunities that can be capitalised upon, and

threats to be mitigated – both potentially more impactful for smaller companies.

From Peter Schwartz, in ‘The Art of the

Long View’, “…small businesses are

even more vulnerable to the kinds of surprises and uncertainties that often

overwhelm the plans of giants.”

But,

first, what is the current state of play? Forecasting, as a systematic

exercise, is largely the preserve of big organisations. One global company that

I worked for employs a team of economists, as well as Market and Financial

Analysts, informing company-wide decisions with their macro- and micro-economic

analysis and forecasts. The likes of Shell and AT&T are famed for their

horizon scanning and scenario planning efforts. This isn’t exclusively so, and

Scwartz gives the example of Smith & Hawken in the US, using scenario

planning to build a successful gardening tool business from scratch.

Indeed,

research from the British Standards Institution (BSI) and the Business

Continuity Institute (BCI) showed that, for 2016, large companies (at 74%) are

more likely to undertake horizon scanning and long-term trend analysis than

SMEs (58%).[6]

Even that figure of 58% seems high to me, certainly in any sort of systematic

fashion – it’s much more likely to be informal.[7]

Encouragingly, that figure is up from 48% of SMEs in the 2013 iteration of this

survey. On a similar discipline, Zurich found that, since the financial crisis,

53% of SMEs are spending more time on risk management; 35% are doing more

long-term financial planning, and 33% are looking at their business continuity

plans more frequently.[8]

But

there’s something else in this research that gets to the crux of my argument

about the competitive advantage to be realised by Challengers and SMEs: the

BSI/BCI found that fully one third of organisations don’t use the results of

their horizon scanning; but, crucially, SMEs were more likely to do so, as 71%

said they use their trend analysis results, against 66% of large organisations.

In the 2014 iteration of the survey, it asked whether respondents had access to

the final output, finding that only 16% did not in firms with up to 250

employees; but that nearly doubled to an average of 29.6% in firms with more

than 250 staff. It is because owners, directors, and senior managers

(decision-makers) in smaller firms will be involved in the horizon scanning

themselves.

SMEs are

less likely to do it, but more likely to use it when they do, and take greater

advantage of it. My central point is one that I have made before: Challengers

and SMEs can gain competitive advantage from forecasting, because they are more

agile, with shorter lead-times between foreseeing an opportunity (or threat)

and going after it (or evading it).

WHAT TO

DO IN YOUR CHALLENGER BUSINESS

So, how

can Challengers exploit this potential competitive advantage: firstly, by being

better than their large competitors at forecasting; and, secondly, by

capitalising on the results more effectively?

Taking

the guidance from the book, the first thing to do is to identify your potential

super-forecasters and assemble them

in a team, given that Tetlock recommends using teams to enhance accuracy[9] –

remember that those in the team should display some characteristics outlined

previously, and be multi-disciplinary. This group of people could have meetings

dedicated to this, or you could incorporate the whole process into existing

meetings.

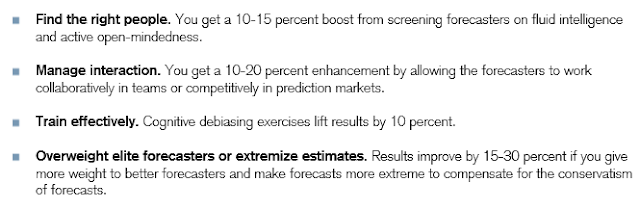

|

| Accuracy factors, from HBR article |

|

| Individual traits of super-forecasters, from Credit Suisse article |

|

| Approach in general, from Credit Suisse article |

Then set

your questions. In the book’s ‘Ten

Commandments’, the first is “triage”:

prioritise, focus on questions that you can answer and action. Start with a

handful of questions that are central to the success, or otherwise, of the

business, and the kinds of questions that could drive changes in behaviour.

Perhaps using Porter’s 5 Forces or the PESTLE framework will help to identify

questions; and these may include some of the following:

|

| One of my forecasts, similar to the above, on the GJP |

The Super-forecasting mantra then outlines

how to proceed: Forecast, Measure, Revise, Repeat – an ongoing, incremental

process. Make your forecasts, monitor them and measure their accuracy, revise

your methodology, and then repeat.

In terms

of how to actually make your forecasts, the book is full of practical advice –

from Fermi estimation, to Bayes’ theorem, from Bayesian question clustering to the

use of probabilities, and add in things like Analysis of Competing Hypotheses

(ACH) and the Delphi technique – and requires reading in full to improve

individual forecasting. But, in general, of course you will have selected a

range of people who are inclined to gather data from various sources (sales

data, competitor analysis, market research, macroeconomic data) – get each to

make a forecast on the question, discuss and debate that and come up with a

company-consensus forecast. Enable the group to continue collecting data for

each question, and re-forecast the next time they meet. All the time throughout

this, flag up anything that requires acting upon by the company.

I did

something similar to this with a university – a Challenger in its sector – last

year, where we addressed the question: what will be the size of our market next

year, in three years, and in 2020? Underlying this is the fact that the number

of 18-year-olds in the UK is declining up to 2021, and particularly so for this

university’s geographical market and discipline specialism. We considered this

alongside higher education participation rates, market share of their courses,

and other factors; with participants working in groups to make their forecasts,

providing us with an organisational consensus.

It

forecast a marginal decline in the size of the market. As a result,

practically, it sharpened people’s focus as they realised that, to grow, they

need to take a greater market share of a smaller market; hence everyone is

looking that much harder for opportunities. The university has done very well

since, including new innovations, product launches, and marketing initiatives.

I don’t think any other organisation in that sector has given as much focus to

this, nor made as comprehensive forecasts, and hence it’s a source of

competitive advantage.

And of

course, getting things like this right can matter – the answers to all of the

questions outlined above need to be planned for. Consider the forecast of

Microsoft CEO Steve Bullmer in 2007 that, “There’s

no chance that the iPhone is going to get any significant market share. No

chance.” Before it went on to hold about 42% of the US smartphone market,

and 13% worldwide. A level of complacent forecasting that contributed to

Microsoft being almost nowhere in the smartphone market. What might be the

equivalent in your industry, and will you see it coming?

In

summary, this is an excellent and, importantly, a very practical book for

improving organisational forecasting. Embedding its lessons in your Challenger

business could be a source of competitive advantage, bearing in mind that there

is no reason that Challengers and SMEs cannot be better than their bigger

rivals – that they can become super-forecasters.

In this, the book is a revelation. And, by doing so, the very least you will

have achieved is to instil a mind-set in your staff of critical analysis about

their external environment – a good thing in and of itself.

If you

want to know more, then read the book. If you want to set up a super-forecasting programme in your

organisation – including team selection, training, question-setting and

management – then contact me here. Meanwhile, if you think you’re up to the

task and want to hone your skills, then you, too, can join the Good Judgement Project here.

|

| My most recent GJP forecast |

[1]

Super-Forecasting, pp.17-18

[4]

Originally derived from the work of philosopher Isaiah Berlin.

[5]

Super-Forecasting, p.231

[7] The sample for this survey is

skewed by the fact that it is carried out by business continuity specialists:

two thirds of respondents were in BC roles, where forecasting is important

(“continuity” is the operative word). It’s also skewed by industry, as well

over half of respondents were in financial/insurance, professional services,

IT, public administration, defence or health. Only 6% in manufacturing or

engineering, only 4% in retail.

No comments:

Post a Comment